“I have roots on both sides”:

Kali’na people’s mobility in the cross-border region

of the lower Maroni River since the 1950s

Marquisar Jean-Jacques

Abstract

The Kali’na are an Indigenous, Carib-speaking people settled along the Guiana coast between Venezuela and Brazil. European colonization and the creation of modern borders fragmented their ancestral territory, particularly affecting those communities along the Lower Maroni River, which today marks the official border between Suriname and French Guiana, an overseas department of France. While the river functions as a political border between these two states, Kali’na people experience it as a connective space linking families, places, and histories. For centuries, Kali’na communities have developed a way of life based on networks of matrimonial alliances, collective land ownership, shamanic cosmovision and mobility. Their mobility has created a multi-sited way of inhabiting space that challenges state control of territory and has enabled them to adapt to the world’s most dynamic muddy coastal environment. Since the mid-20th century, sedentarization pressures have grown as Kali’na communities became citizens of nation-states. Yet their mobility persists within and beyond the Lower Maroni region and remains central to cultural continuity and resilience. Drawing on recent ethno-geographic research, this article highlights how Kali’na mobility encompasses intertwined and overlapping experiences in which the coast, rivers, social networks and political contexts simultaneously function as both supports and drivers of circulation. People’s lives are paced by periods of voluntary and involuntary mobility, making movement a defining and enduring feature of Kali’na existence and reinforcing an underlying common experience of mobility.

Résumé

Citer cet article

Jean-Jacques, Marquisar. 2025. « “I have roots on both sides”: Kali’na people’s mobility in the cross-border region of the lower Maroni River since the 1950s». Nomopolis 3

The Kali’na are a transnational Indigenous people of the Carib language family settled along the Guiana coast from Venezuela to Brazil. Due to European colonization and the arbitrary imposition of borders in this region, part of the population established in the lower Maroni River area are divided between the territories of French Guiana and Suriname. The Maroni River marks the political boundary between Suriname and French Guiana (an overseas territory of France), but for the Kali’na, it is experienced as a contiguous territory because related families live on both banks. Since the mid-20th century, the Kali’na of the lower Maroni River have experienced a rapid process of sedentarization and assimilation, becoming nationals of distinct states. However, these transformations have not put an end to the Kali’na mobility within and beyond the lower Maroni region, nor does this mobility contradict their territorial rootedness or their attachment to places that are central to their cultural identity.

Mobility is a polysemous term in the social sciences (Ortar, Salzbrunn, and Stock 2018). In response to contemporary Indigenous realities, scholars have framed mobility as relational, political, and place-based, emphasizing how movement is central to Indigenous life and survival, knowledge systems, and territorial belonging (Allard 2020; Mezzanotti and Kvalvaag 2022; Miller 2019; Salazar and González 2021; Trujano 2008). Drawing on my positionality as both a member of the Kali’na communities and a native of the lower Maroni region, I approach mobility not merely as movement through space, but also as a relational experience entangled with colonial histories, territorial belonging, and community knowledge systems. I consider mobility as a process in which people’s movements accumulate into complex circulations underpinned by networks of places and actors. These movements affect space as well as individuals and carry social meanings (Bonerandi 2004; Stock 2004). Kali’na mobilities have their own spatiality and temporality, resulting in a polytopic (Stock 2004, 2006) or multisited way of inhabiting, which is rooted in their geographic mobility. Kali’na polytopic inhabiting is connected to a network of places and people and is underpinned by socio-economic and cultural activities that challenge state control of the Maroni River cross border region. Mobility forms the basis of Kali’na socio-spatial organization and has enabled them to adapt to socio-environmental changes, as well as to shape places and cross-border space.

This article analyzes the spatial mobility of the Kali’na since the 1950s as a process that has oscillated between voluntary and forced movements — movements that are experienced unequally between individuals. I have chosen this timeframe because the early 1950s was a period of significant political transformation for both Suriname and French Guiana. Suriname gained increased autonomy from the Netherlands—eventually achieving full independence in 1975 (Hoefte 2014)—while French Guiana transitioned from a French colony to an overseas department of France in 1947 (Maurice 2022). In the lower Maroni region, an important penal colony that had occupied Kali’na ancestral lands was also dismantled around this time (Sanchez 2014). During the same period, aerial photography began to clearly document coastal fluctuations and the dynamics of human settlements in both countries, enabling a more precise assessment of socio-environmental transformations in the region.

This analysis is informed by recent ethno-geographic research I conducted between Marsh 2021 and January 2023 in the communities of Awala-Yalimapo (French Guiana) and Galibi (Suriname), undertaken as part of my doctoral research at the University of French Guiana[1]. It relies on 66 interviews and 23 months of participatory and non participatory observations of the spatial mobility practices among Kali’na inhabitants of the lower Maroni – a people to whom I belong through kinship ties and a region where I was born. Given these forms of belonging, my positionality facilitated access to locally embedded knowledge and informed the interpretation of mobility as a practice shaped by colonial histories, ecological change, strategies of survival, and continuity. Drawing on selected examples of mobility, this paper demonstrates that, in the context of the Kali’na of the lower Maroni, mobility encompasses a range of intertwined and overlapping experiences, in which the coast, rivers, social networks and political contexts simultaneously function as both supports and drivers of circulation.

The first part of the article explores Kali’na environmental mobility as a key practice of inhabiting space, one that has enabled them to adapt to the fluctuations of the world’s most dynamic muddy coastline. However, contemporary French land planning policies and processes of sedentarization have increasingly created resistance to movement on Kali’na communities on the French side of Maroni River. The second part examines how experiences of forced mobility in response to disruptive events can also become sources of resilience for Kali’na individuals and communities. These episodes of constrained movement highlight the community’s ability to leverage the (f)utility of the political border to serve their own interests.

I- KALI’NA MOBILE LIFESTYLE ON THE WORLD’S MOST DYNAMIC MUDDY COAST: FROM TRADITIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL MOBILITY TO CONTEMPORARY COASTAL DISPLACEMENT

Much existing research portrays Indigenous peoples as vulnerable to environmental change, a framing that overlooks the diverse and complex ways in which Indigenous communities interpret, engage with, and respond to these transformations— revealing the variation of vulnerability and resilience across time and space (Ford et al. 2020). In the lower Maroni River region, the Kali’na have, for centuries, developed a traditional form of environmental mobility to adapt to coastal fluctuations. In the context of the Anthropocene and the global climate crisis, the Kali’na historical environmental mobility offers a compelling example of a nuanced image of Indigenous vulnerability in the face of environmental change.

The lower Maroni region is part of a coastal system characterized by the episodic movement of large mudbanks, which drive cycles of coastal advance and retreat. This unique dynamic makes the Guiana coast the longest and most active muddy coastline in the world (Toorman et al. 2018). The mudbanks that form near Cape Cassiporé (north of the state of Amapá) are constituted of sediments discharged by the Amazon River, which are transported westward and continuously reworked by swell and coastal currents such as longshore drift and tidal currents. The mudbanks ultimately dissipate when they reach the Orinoco Delta (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Mudbank circulation along the coastal plain of the Guianas. Map by author. Source: redrawn from Allison & Lee, 2004, p170

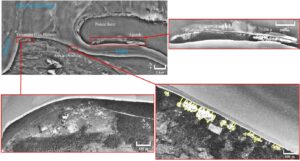

Throughout their history, the Kali’na of the lower Maroni have learned to live with this highly dynamic coastline by developing a form of environmental mobility that has allowed them to sustain their subsistence activities such as fishing, hunting, and gathering by relocating their settlements in reaction to shoreline fluctuations. Thanks to aerial photographs of French Guiana’s coast from the 1950s, geomorphologists have been able to quantify the rates of long-term coastal retreat. These images also document the coastal occupation and movements of Kali’na families from the Pointe Isère peninsula, a historical landform near the Maroni River mouth that later disappeared due to coastal dynamism (Plaziat and Augustinus 2004), to the continental shore (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Aerial photographs showing the coastal area occupation in 1955. Represented in yellow are the different families’ settlements. Source: IGN, remonter le temps.

This relocation was made possible by the closure of the prisons located at the mouths of the Maroni and Mana rivers (Heuret 2018) and the transition of French Guiana from a colony to a fully integrated department of France (Maurice 2022). Between 1852 and 1953, France maintained penal colonies throughout French Guiana, including the lower Maroni River, an area which had been long occupied by the Kali’na and their ancestors (Collomb and Tiouka 2000). To distance themselves from the penal system, the Kali’na on the French side of the river relocated to the left bank of the Maroni (in Suriname) and to Pointe Isère, where they established socio-economic ties with Creole[2] communities, with whom they cohabited (Collomb and Tiouka 2000). In 1947, shortly after the closure of the nearby penal colonies, the Prefect[3] Vignon visited Pointe Isère accompanied by Catholic missionary Father Le Lay to attempt to convince the residents to move across the Mana River, since the area was becoming increasingly uninhabitable due to erosion, sediment buildup and the salinization of freshwater wells. Yet, behind this semblance of humanitarian action lay a strategy of state control that aimed to restrict the mobility of the highly mobile Kali’na and encourage them to sedentarize their villages. Their traditional mode of inhabiting space and its relation to the dynamic nature of the coastline were not considered by the prefect or the French government that he represented.

Although they did relocate from Pointe Isère to the mainland communities of Awala and Yalimapo, and ultimately became increasingly sedentary, the Kali’na did not forget the inherent fluctuations of their coastline. They had long developed expertise in understanding coastal changes and sustainable ways of coexisting with them. One technique for dealing with episodes of intensive erosion is for families living on the waterfront to relocate their homes further inland, which many did when severe erosion struck the village of Awala in the late 1980s (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Changes in the Mana River estuary between 1988 and 2013 in front of Awala. Photos courtesy of Marie-Thérèse Prost and Daniel Payeur

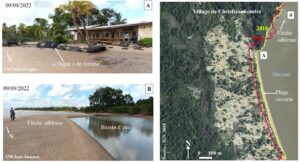

Similar processes have played out in other areas, although not always with the same results. On the other side of the Maroni River in Suriname, the community of Galibi is situated near the river’s mouth, where the villages of Langamankondre and Christiaankondre are located. The site supports fishing activities and is only accessible by canoe, since no road connects it to the rest of the country (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The community of Galibi comprised of the villages of Langamankondre and Christiaankondre. Photo courtesy of Dustin Refos

In these villages, the Kali’na have also relocated multiple times in response to episodes of erosion and chronic flooding. The remains of concrete houses are visible at low tide along the riverbank, where some inhabitants have attempted to build dikes to protect houses from coastal retreat (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The beach of Christiaankondre in 2022. The yellow line shows the shoreline in 2018; the red one shows the shoreline in 1950

In the past, dwellings in all of these Kali’na communities were generally constructed in the form of “carbets”. This local French term designates lightweight, often open-sided structures built directly on sandy soil using natural materials such as palm leaves and wooden posts (Figure 6). Villages were organized into residential clusters typically inhabited by a nuclear couple and their descendants and bound by interdependent relationships. The structure of the household plot evolved over time, depending on the departure of sons or daughters and the integration of sons- and daughters-in-law (Jean-Jacques 2024; Kloos 1971).

Figure 6: Evolution of the landscape between the village of Yalimapo between 1977 and 2022. Photo courtesy of Jacques Fretey and Roger Leguen

During episodes of erosion, the lightness and portability of these traditional structures—combined with strong family solidarity and empirical knowledge of environmental changes—enabled the Kali’na to remain resilient over generations. Carbets could easily be abandoned or reconstructed without a significant loss or expense of energy and resources. This mode of inhabiting space facilitated the community’s adaptation to their unique local environment and fostered a form of co-mobility between the coastline and its inhabitants.

Today, the relevance of this long-standing co-mobility has become increasingly difficult to sustain, as housing has become denser along a narrow sandy strip wedged between the sea and the swamps that limits the possibilities for retreat or spatial reconfiguration in response to environmental change (Figure 6). Over time, the Kali’na of Awala-Yalimapo have also become integrated into a consumer society, and the French government has encouraged them to adopt more permanent concrete housing connected to water and electricity networks, a significant contrast with the lightness and portability of their traditional housing structures (Figure 6).

A final key change to Kali’na habitation patterns occurred in 1988 in response to French Guiana’s Indigenous rights movement, which was largely driven by Kali’na activists. In a partial recognition of their demands for increased autonomy, the villages of Awala and Yalimapo were officially established as a French commune. Since then, Awala-Yalimapo has been a commune where most inhabitants are Kali’na, and the municipal council is likewise composed predominantly of Kali’na representatives. This new status brought to the Kali’na of these villages a full range of local public services, administrative complexities, political responsibilities and new forms of governance (Chalifoux 1992; Collomb and Tiouka 2000). This new status provided the community with an opportunity to enter the political landscape of French Guiana and played a significant role in the recognition of their land rights through the ZDUC system (Zones of Collective Use Rights) system[4], a legal framework unique to France (Davy et al. 2014, 2016). However, this land status is increasingly showing its limitations considering the evolving lifestyles of Kali’na people. Awala-Yalimapo remains subject to French planning and construction regulations. These regulations sometimes conflict with the Kali’na’s spatial organization, which continues to be shaped by kinship networks, fluid mobility, subsistence activities, traditional ecological knowledge, and spirituality—despite the many socio-cultural, political, and economic transformations of the past seventy years.

The fluidity of Kali’na settlement patterns comes into friction with that of the French State, particularly regarding current approaches to inhabiting coastal spaces. The French government requires coastal municipalities to proactively anticipate shoreline retreat and enforces planning regulations that are generally disconnected from local realities. In the case of Awala-Yalimapo, national authorities and their agencies do not perceive coastal erosion as an urgent matter, in contrast to local elected officials. This tension is further reinforced by the colonial legacy of a hierarchical governance system, the multiplicity of actors involved, heavy bureaucratic procedures and extended decision-making timelines. In France’s legal system, the coastline is part of the public maritime domain, which encompasses the shore and the sea (Chadenas, Rollo, and Desse 2016; Le Roy 1992; Prieur 2012). Regardless of the Kali’na’s centuries-long history of settlement and management of the French Guiana coast, they do not have any ownership of these traditional lands. They are also not formally recognized as indigenous peoples (Sommer-Schaechtelé 2023), since this categorization is in conflict with core aspects of the French constitution and legal system, which, based on a universalist interpretation of equality, acknowledges only French citizens “without distinction of origin, race or religion”[5]. All these elements have reduced the room for maneuver that inhabitants once had through traditional coastal mobility and management.

However, thanks to its status as a municipality (commune), the elected officials of Awala-Yalimapo were able to revise the urban planning documents in 2021 and explicitly express their intent to relocate residents from Yalimapo to Awala in response to alarming levels of coastal erosion. Since 2019, the sea has washed away nearly one hundred meters of shore, while coastal flooding has become a chronic phenomenon. Although this relocation plan was approved by the French State in 2022, it remains contentious among residents, many of whom do not share the same perception of an environmental “emergency” or the existence of coastal risks and change anticipated by their elected officials. When I questioned residents about their perspective on coastal changes, some residents invoked their attachment to place and stated a refusal to leave unless erosion or flooding poses a direct and immediate threat to their homes. These sentiments are clearly illustrated by the remarks of a couple in their fifties living in Yalimapo in April 2022:

Husband: “In October 2019, I remember the day the sea started to rise. It reached the carbet that sells handicrafts and the road. It happened in the afternoon, around 4 p.m., something like that.”

Me: “How did the residents react?”

Wife: “People were like, ‘Oh my God, what is this?!’ They were surprised, yes, and afraid.”

Me: “And now, is it all forgotten? Is there no more fear?”

Husband: “No, we’re still afraid—we’re the ones living right in front of the sea, after all. But for now, nothing’s happening, so I’ll stay here. When the sea starts entering my house, that’s when I’ll move. I’ve been here for 59 years. I was born here—I like to joke that I’m a pureblood from here. My umbilical cord is buried here. I’ll die here.”

Having the decision to relocate made by political representatives is unprecedented, yet it follows the historical trajectory of environmental mobility among the Kali’na of the lower Maroni. However, the political and administrative nature of this decision marks a break from the traditional model of environmental mobility, which was voluntary, based on self-organization, and involved case-by-case assessments of the appropriate moment to move in response to coastline change.

This decision has also been experienced negatively by some residents, since the relocation is being delegated to and managed by institutional actors from whom they feel socially and geographically distant. It is difficult for them to envision this future displacement, especially given that no development has begun at the relocation site, there is uncertainty around financial compensation, and the progression of coastal erosion remains unpredictable.

The former local system of environmental mobility practiced by the Kali’na is not acknowledged as valid by the French state, which imposes its own timelines and conditions for environmental relocation. This denial constitutes a form of epistemic violence and reflects what Malcom Ferdinand (2019) calls a “colonial inhabiting,” contributing to territorial dispossession and fueling a resistance to mobility. What was once a traditional, freely chosen form of mobility has now become a future displacement perceived as imposed and constrained. Ultimately, the shifting socio-political and environmental context is reshaping the co-mobility that once defined the relationship between the inhabitants and their coastal environment.

II-FROM ONE BANK TO THE OTHER: CONSTRAINED MOBILITY AS A SOURCE OF RESILIENCE AND THE (F)UTILITY OF POLITICAL BORDERS

In addition to environmental factors, Kali’na mobility is also deeply rooted in the socio-cultural dynamics specific to their society, such as matrilocal residence, internal conflicts that lead to the division and renewal of residential groups, spiritual ceremonies and celebrations. In the colonial and post-colonial context of Suriname and French Guiana, the lower Maroni region has gradually become a cross-border space in which the Kali’na have adapted their traditional mobility to the political and social transformations that have shaped their lives. The Maroni River, together with other waterways such as the Mana and Oyapock rivers, has long constituted a continuous region stretching across Suriname, French Guiana and Brazil that has structured Kali’na circulation, connected kinship networks, and embedded historical events and identity. Due to colonization, however, the Maroni and the Oyapock rivers had also come to represent discontinuity, marking the divide between political, economic and cultural systems shaped by different European colonial powers.

From 16th century onward, the introduction and mobilization of the concepts of “terra nullius”, then “nation-state” and “citizenship” by Europeans empires in the Guianas led to land dispossession and the negotiation of geopolitical borders. As with other places colonized by the European empires, mobile Indigenous peoples were often perceived as wanderers without political structure, land planning and ownership or attachment to a homeland (Russell 2018). After centuries of competition and conflict in the region between the French, Dutch, Portuguese and English empires, the Maroni River eventually crystalized as a line of demarcation between Dutch Guiana (Suriname) and French Guiana in 1891. Due to the pressures of colonization, in the mid 19th century th century the Kali’na population in French Guiana was at the lowest level of their history, about a hundred people (Abonnenc, Le Lay, and Lecoq 1956).

In the late 19th century, the French and the Dutch intensified their spatial occupation of the lower Maroni River region with the creation of the trading outpost of Albina on the Dutch side and the penal colony of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni on the French side (Kloos 1971). The Kali’na’s demographic weakness and the colonial expansion cause them to lose control of a vast ancestral territory that once connected to indigenous kinship and trade networks across the Guianas (Collomb and Tiouka 2000). By the turn of the 20th century, the lower Maroni Kali’na lived in isolated communities composed of groups of families who over time had less regular contact with other Kali’na communities in the neighboring colonies. Some Kali’na families resettled in different villages on both sides of the Maroni River mouth and in the lower Mana River in French Guiana. They became more dependent on trade exchange with colonial society and started to progressively sedentarize (Collomb and Tiouka 2000).

However, after 1946 the situation changed for the Kali’na of the lower Maroni River region. French Guiana became a department, partly due to the local Creole bourgeoisie advocating for assimilation with mainland France and demanding the same rights as other French citizens (Maurice 2022). The Kali’na of French Guiana started to be assimilated into the French post-colonial society, including the government sedentarization policy, the granting of French citizenship to Indigenous people in 1964, and the establishment of Catholic boarding schools in the 1930s led by missionaries and supported by the French government (Armanville 2012). As Russell (2018:165) has pointed out for the case of the Aboriginal peoples of Australia, the same idea of “containing Indigenous people and managing Indigenous mobility” as part of a “civilizing mission” existed in French Guiana and Suriname, where evangelism was disguised as schooling. The Catholic Church and affiliated religious orders played a key role in the colonization of French Guiana. They actively contributed to the processes of racialization and assimilation of local populations while benefiting from the complicity and sustained support of the colonial administration (Campolo 2025; Donet-Vincent 2006; Fuggle and Greene 2025; Moomou 2009). Many Kali’na from Pointe Isère village and the Mana River went to the boarding schools after the missionaries convinced their families to entrust their children to them or used police to enforce their attendance in some cases (Ferrarini 2022). Some of these children lived on the Surinamese border and attended boarding school in French Guiana while their parents continued to move from one bank to the other to pursue rotational agriculture (locally called the abattis system), salaried seasonal jobs and internal socio-cultural dynamics.

According to some Kali’na interlocutors who were children at that time, they experienced boarding school as a form of colonial constrained mobility. They were separated from their parents at a young age and came back to visit their family only for short holidays, which made them move regularly between their Catholic schools and their villages (Armanville 2012; Ferrarini 2022). At the end of their schooling, many girls came back to their village especially because parents arranged marriages for them. Many Kali’na recognized that boarding schools had negative impacts on their lives, particularly because of the socio-cultural disruption they caused. However, the granting of French citizenship and the schooling of Kali’na youth in the boarding schools also lead later on to the emergence of a new generation of men and women more educated than their elders and far more competent in the French language, which is critical for political action and social mobility in France.

This later generation of Kali’na worked to reappropriate the civil and political rights that accompanied their citizenship (Collomb 2005). These two elements allowed the accumulation of social capital and the expansion of political and relational networks, including connections with French social science researchers, for example, with whom an awareness of the Indigenous conditions within the French colonies and Suriname was reinforced (Guyon 2009). As a result, the most enterprising and influential Kali’na families have gained visibility in the French Guianese and Surinamese political scenes and accumulated social, cultural and symbolic capital (Bourdieu 1986), which circulates and is transmitted through generations over time (Jean-Jacques 2024). Thus, in this specific case of the boarding schools, constraints to physical mobility have paradoxically led to social mobility, power and prestige for some Kali’na, demonstrating their resilience after a traumatic event.

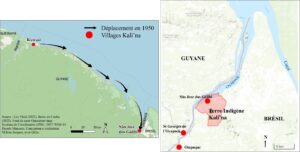

Constrained mobility has also occurred because of Kali’na people’s spontaneous regulation of population densities, resource access and social relations, including matrimonial alliances and conflicts. In the past, larger communities used to divide into smaller groups due to interpersonal quarrels which sometimes instigated vendettas, shamanic attacks or other forms of aggression within or between families. As anthropologists have demonstrated for other segmental societies in Amazonia, division usually helps to avoid the escalation of violence while maintaining a minimum of cohesion between the groups within a larger social system (Descola 2005; Dreyfus 1992; Rivière 1984). This mechanism applies to the Kali’na of the lower Maroni River region. However, if scission has at times reduced tensions between kinship groups, at other times it has also provoked forced mobility, a reaction that is fully integrated in the social construction of the Kali’na collective identity. This was the case in 1950, for example, when 38 Kali’na from Kuwasi village on the Mana River decided to move by boat and settle in the village of São José dos Galibi on the Brazilian side of the Oyapock River in Brazil (Figure 7). According to the people who experienced this migration and their descendants, there were multifactorial reasons for the move, including internal conflict and tension with the French state (Arnaud 1966; Bento da Cunha 2022; Santos 2020; Vidal 2023).

This migration was organized by Mr. Lod, who was a Kali’na nurse working for the French government. He refused to send his children to the boarding school in Mana town and protested the absence of a school in Kuwasi village. Before he led his people to Brazil, he made a first trip there to meet the Brazilian administrators who could help his community to settle (Vidal 2023). The testimony of one of the granddaughters of the first arrivals also recounts that they were seeking recognition of Indigenous rights (Santos, 2020), since Brazil committed to that path by creating the Indian Protection Service (today called the FUNAI[6]) in 1910 (Křížová 2022; Rivet 1913). For some of my interlocutors in Awala-Yalimapo, it was the succession of inter-family conflicts that led to the gradual breakup of this village and the departure of people to different regions in western Guiana, Suriname and Brazil. The French government tried to prevent these families to leave by offering them better options to stay, but failed (Vidal 2023). On the other side, the Brazilian government seized the opportunity to welcome these Kali’na people and gave them land, partly to enhance the Brazilian presence in a border region that was historically disputed with the French empire in the 19th century (Bento da Cunha 2022; Granger 2011) (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The journey from Kuwasi to Sao José in 1950 (on the left). The new Kali’na village location in Brazil (on the right). Source: https://terrasindigenas.org.br/es/terras-indigenas/3669

Whatever the reasons of their movement, crossing rivers and navigating along the coast to find a “better land” was not something new in the Kali’na historical mobile lifestyle, because liquid spaces are not seen as physical borders but as fluid bridges and routes between lands. Moreover, this group of migrants played on the political border system and the inherent tensions between nation-states that it represents by using borders as a useful opportunity instead of letting them confine them to one place. However, today this community is fully integrated in the nation-state of Brazil and benefits from Indigenous policies there, while they maintain contacts with their relatives who stayed in Suriname and French Guiana.

A more recent example of how the Kali’na leverage their mobility and transnational family networks as a source of resilience can be seen in their response to the Surinamese Interior War (1986-1992)[7]. After gaining autonomy in 1954 and full independence in 1975, Suriname faced a turbulent post-colonial transition characterized by inter-ethnic tensions, corruption, the formation of ethnically based political parties, and a severe economic crisis. The Interior War, which unfolded in the region around Albina and upstream along the Maroni River, was rooted in ethnic divisions. It opposed the Maroon militia led by Ronnie Brunswijk—a Djuka[8] former soldier—against Desire Bouterse, the head of the national army (Hoefte 2014; Hoogbergen and Kruijt 2005; Vries 2005). Indigenous people living in villages near the conflict zones were forced to flee to French Guiana from 1986 onwards. This constrained relocation affected many Surinamese Kali’na, some of whom took refuge in Awala-Yalimapo after 1986. The newly established municipality of Awala-Yalimapo, created in December 1988, welcomed several families at the time. Leaders of the Association of the Indigenous Peoples of French Guiana (AAGF), along with village chiefs, locally coordinated the reception of these Kali’na families to prevent their settlement in refugee camps, as was the case for most Maroon migrants (Bourgarel 1989; Guyon 2010). The chiefs of Awala and Yalimapo allocated land parcels based on relational affinities and kinship ties with the Kali’na from Suriname (Jean-Jacques 2024).

Many Kali’na drew upon their transnational family networks to cross the border and rebuild their lives in French Guiana, mainland France, or the Netherlands (Uitermark 2021). These family networks played a crucial role in this process, as the Kali’na matrimonial system facilitates partner mobility, which contributes to the expansion and revitalization of community settlements. In the lower Maroni River region, men and women can settle in their spouse’s village, which is structured around extended family constellations and integrated into broader kinship networks (Kloos 1971). Thus, this matrimonial mobility not only reconfigures alliances and strengthens socio-cultural continuity among individuals and communities across distant villages but also facilitates forced displacement during times of crisis. Many Kali’na of the lower Maroni region proudly display their belonging to both riverbanks and their transnational identity, such as Mr. Tococo, an inhabitant of Manepili village, who I interviewed in July 2021: “My father was from Suriname, originally from Bigi Poika. My mother was from Bellevue, but she was born in Rocoucoua, and I am from the Maroni. What I mean is that I have roots on both sides.”

During the Surinamese conflict, the political border was both futile as a political boundary and useful for the Kali’na of Suriname, who had traditionally moved freely across the river as part of their mobile way of life. The Interior War not only reinforced their capacity to cross borders but also highlighted the broader international challenges faced by transboundary mobile Indigenous peoples in asserting their rights to freedom of movement and security (Calí Tzay 2024). Despite their displacement due to conflict, France never recognized the Surinamese Kali’na or the Maroons as refugees. Rather, they were officially classified as “provisionally displaced persons from Suriname” (PPDS) (Bourgarel 1989). While this status might be interpreted as consistent with the Kali’na’s historically mobile way of life, it failed to reflect that many of them settled permanently in French Guiana or to acknowledge their transboundary Indigenous identity and historical ties to the territory. They continue to be stigmatized as immigrants, even if some of them were granted with French citizenship, rather than being recognized as long-term residents or members of transboundary Indigenous communities.

This gap highlights the limits of state migration policies, which reinforce national borders under the guise of sovereignty and clash with the Indigenous principle of territorial continuity. Despite the existence of international frameworks advocating for Indigenous peoples’ rights to access their ancestral lands and resources across national boundaries, the Kali’na of Suriname and French Guiana do not enjoy official recognition of their cross-border mobility. Neither Suriname nor France formally recognize the political category of “Indigenous peoples” (Kambel 2007; Sommer-Schaechtelé 2023) and both disregard the definitions established by the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Convention No. 169 in 1989 and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007. While France has adopted the UNDRIP, its non-legally binding nature—unlike that of ILO Convention 169—grants states greater discretion in its interpretation, often to the detriment of Indigenous communities’ interests.

CONCLUSION

Mobility has been a historical asset and internalized social practice among the Kali’na for centuries. They moved and continue to move for various reasons such as maintaining cultural practices, finding resources, seeking economic opportunities, or asserting their rights to self-determination. Mobility is still an important element of their contemporary lifestyle despite coastal change, land dispossession, sedentarization, international borders and conflicts. Their historical patterns of movement between and across borders predate the formation of nation-states in this region. Rather than letting socio-environmental transformations disrupt their lifestyle, the Kali’na integrated them with their patterns of mobility, whether it is voluntary or forced. Their collective or individual journeys in the cross-border region of the Maroni River and beyond are crucial to the weaving of community bonds between scattered family groups.

For the Kali’na, the Maroni River and other major waterways have been a double-edged sword—offering subsistence, refuge, places for relocation, and mobility, while also serving as sites of conflict and forced displacement during turbulent times. The ability to move from one riverbank to the other has enabled them to accumulate what can be described as a capital of mobility (Kaufmann 2004). Mobility has given space to exchanges that are central for knowledge production and acquisition among the Kali’na, yet this form of capital was gained through significant socio-cultural disruption and the dispossession of ancestral lands, as colonial expansion and assimilation processes have profoundly impacted and continue to undermine Kali’na people’s ways of life. Nonetheless, mobility has been an ambiguous and varied experience among individuals. While some associate it with traumatic consequences, others perceive it as a source of resilience, offering access to social mobility and improved living conditions. However, this form of capital is unevenly distributed among the Kali’na of the lower Maroni, particularly along lines of gender, age, and socio-economic resources. Moreover, access to mobility fluctuates over the course of an individual’s life; periods of (in)voluntary immobility can occur due to changing personal or structural circumstances. In a rapidly shifting global context, mobility demands constant adaptation, which requires not only individual flexibility and knowledge but also access to new technologies and financial means in order to sustain movement. For the Kali’na, mobility has been and continues to be a great asset for building resilience in the face of a constantly changing world.

References

Abonnenc, E., Y. Le Lay, and H. Lecoq. 1956. “Démographie de la Guyane française. III : Les Indiens Galibi.” Journal de la société des américanistes 45(1):195–208.

Allard, Olivier. 2020. “Fuites frontalières entre le Guyana et le Venezuela : migrations et contrebande dans un village amérindien.” Cahiers des Amériques latines (93):29–48.

Armanville, Françoise. 2012. “Les Homes Indiens En Guyane Française. Pensionnats Catholiques Pour Enfants Amérindiens 1948-2012.” Aix-Marseille Université, Aix-en-Provence.

Arnaud, Expedito. 1966. “Os Índios Galibí Do Rio Oiapoque; Tradição e Mudança.” Boletim Do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi-Antropologia (30).

Bento da Cunha, Evilania. 2022. “Dinâmica Territorial Do Povo Galibi Kali’na de Oiapoque-AP.” Universidade Federal do Pará.

Bonerandi, Emmanuelle. 2004.“Archive. De la mobilité en géographie.” École normale supérieure de Lyon.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” Pp. 241–58 in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Westport: CT: Greenwood.

Bourgarel, Sophie. 1989. “Migration sur le Maroni : les réfugiés surinamais en Guyane.” Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 5(2):145–53. doi:10.3406/remi.1989.1025.

Calí Tzay, José Francisco. 2024. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. A/79/160. United Nations.

Campolo, Victor. 2025. “Faire l’apostolat Dans Le Territoire de l’Inini : Les Pères Spiritains Au Contact de Populations Éparses. Une Approche Spatiale de La Mission (1927-1939).” Social Sciences and Missions.

Chadenas, Céline, Nicolas Rollo, and Michel Desse. 2016. “Les 50 pas géométriques dans les territoires ultramarins.” Les Cahiers Nantais (2):43–52.

Chalifoux, Jean-Jacques. 1992. “Ethnicité, pouvoir et développement politique chez les Galibis de la Guyane française.” Anthropologie et Sociétés 16(3):37–54.

Collomb, Gérard. 2005. “De La Revendication à l’entrée En Politique (1984-2004).” Ethnies (31–32):16–29.

Collomb, Gérard, and Félix Tiouka. 2000. Na’na Kali’na : une histoire des Kali’na en Guyane. Matoury: Ibis Rouge éditions.

Davy, Damien, Geoffroy Filoche, Françoise Armanville, and Armelle Guignier, eds. 2014. Zones de Droits d’Usage Collectifs, Concessions et Cessions En Guyane Française : Bilan et Perspectives 25 Ans Après. Cayenne: Rapport d’étude, Observatoire Hommes/Milieux “Oyapock”,

Davy, Damien, Geoffroy Filoche, Armelle Guignier, and Françoise Armanville. 2016. “Le droit foncier chez les populations amérindiennes de Guyane française : entre acceptation et conflits.” Histoire de la justice (26):223–36.

Descola, Philippe. 2005. Par-delà nature et culture. Paris: Gallimard.

Donet-Vincent, Danielle. 2006. “Le rôle des Jésuites dans les débuts des « bagnes » coloniaux de Guyane.” Criminocorpus. Revue d’Histoire de la justice, des crimes et des peines.

Dreyfus, Simone. 1992. “Les Réseaux politiques indigènes en Guyane occidentale et leurs transformations aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles.” Homme 32(122–124):75–98.

Ferdinand, Malcom. 2019. Une Écologie Décoloniale. Penser l’écologie Depuis Le Monde Caribéen. Paris: Seuil.

Ferrarini, Hélène. 2022. Allons enfants de la Guyane : éduquer, évangéliser, coloniser les Amérindiens dans la République. Paris: Anacharsis.

Ford, James D., Nia King, Eranga K. Galappaththi, Tristan Pearce, Graham McDowell, and Sherilee L. Harper. 2020. “The Resilience of Indigenous Peoples to Environmental Change.” One Earth 2(6):532–43.

Fuggle, Sophie, and Alexander M. Greene. 2025. “Colonial Chess Pieces? Situating ‘Opération Hmong’ in French Guiana within the Wider History and Legacy of the BUMIDOM.” Modern & Contemporary France:1–21.

Granger, Stéphane. 2011. “Le Contesté franco-brésilien : enjeux et conséquences d’un conflit oublié entre la France et le Brésil.” Outres-Mers. Revue d’histoire (372–373):157–77.

Guyon, Stéphanie. 2009. “L’entrée En Politique d’un Village Amérindien de Guyane. Ethnographie d’un Conflit Entre Autorité Coutumière et Mairie.” in Luttes autochtones, trajectoires postcoloniales (Amériques, Pacifique), edited by B. Bosa and E. Wittersheim. Paris: Karthala.

Guyon, Stéphanie. 2010. “Du Gouvernement Colonial à La Politique Racialisée : Sociologie Historique de La Formation d’un Espace Politique Local (1949-2008), St-Laurent Du Maroni, Guyane.” Université Paris 1.

Heuret, Arnauld. 2018. Les Camps Annexes de La Colonie Pénitentiaire Du Maroni. Service patrimoine de St-Laurent-du-Maroni.

Hoefte, Rosemarijn. 2014. Suriname in the Long Twentieth Century. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Hoogbergen, Wim S. M., and Dirk Kruijt. 2005. De Oorlog van de Sergeanten: Surinaamse Militairen in de Politiek. B. Bakker.

Hurault, Jean-Marcel. 1961. Les noirs réfugiés Boni de la Guyane française. Dakar: IFAN.

Jean-Jacques, Marquisar. 2024. “Modes d’habiter, Dynamique Côtière et Production d’un Territoire Littoral Transfrontalier Par Des Kali’na Du Bas-Maroni Depuis 1950.” Université de Guyane, Cayenne.

Jolivet, Marie-José. 1997. “La créolisation en Guyane : Un paradigme pour une anthropologie de la modernité créole.” Cahiers d’Études africaines 37(148):813–37. doi:10.3406/cea.1997.1834.

Kaufmann, Vincent. 2004. “La mobilité comme capital ?” Pp. 25–41 in Mobilités, fluidités… Libertés ?, Travaux et recherches, edited by B. Montulet. Bruxelles: Presses universitaires Saint-Louis Bruxelles.

Kambel, Ellen-Rose. 2007. “Land, Development, and Indigenous Rights in Suriname: The Role of International Human Rights Law.” Pp. 69–80 in Caribbean Land and Development Revisited, edited by J. Besson and J. Momsen. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Kloos, Peter. 1971. The Maroni River Caribs of Surinam. Amsterdam: Van Gorcum.

Křížová, Markéta. 2022. “L’explorateur tchèque Alberto Vojtěch Frič et ses efforts pour protéger les indigènes brésiliens au début du XXe siècle : essai d’histoire croisée.” Brésil(s). Sciences humaines et sociales (4).

Le Roy, Richard. 1992. “La Construction Juridique Du Littoral.” Université de Bretagne Occidentale.

Maurice, Edenz. 2022. Guyane, La Promesse Républicaine Faire France Outre-Mer, 1920-1980. Paris: Les Indes Savantes.

Mezzanotti, Gabriela, and Alyssa Marie Kvalvaag. 2022. “Indigenous Peoples on the Move: Intersectional Invisibility and the Quest for Pluriversal Human Rights for Indigenous Migrants from Venezuela in Brazil.” Nordic Journal of Human Rights 40(3):461–80.

Miller, Douglas K. 2019. Indians on the Move: Native American Mobility and Urbanization in the Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

Moomou, Jean. 2009. “La mission du père Brunetti chez les Boni de la Guyane française à la fin du xixe siècle. Entre évangélisation et stratégie d’approche du colonisateur français.” Histoire et missions chrétiennes 12(4):115–44.

Moomou, Jean. 2011. “Boni et Amérindiens : relations de dominants /dominés et interculturelles en Guyane (fin XIXe siècle : années 1990).” Outre-Mers. Revue d’histoire 98(370–371):273–99.

Ortar, Nathalie, Monika Salzbrunn, and Mathis Stock. 2018. “Conclusion : Reconceptualiser migration, circulation et mobilité.” Pp. 191–200 in Migrations, circulations, mobilités : Nouveaux enjeux épistémologiques et conceptuels à l’épreuve du terrain, Sociétés contemporaines. Aix-en-Provence: Presses universitaires de Provence.

Plaziat, Jean-Claude, and Pieter Augustinus. 2004. “Evolution of Progradation/Erosion along the French Guiana Mangrove Coast : A Comparison of Mapped Shorelines since the 18th Century with Holocene Data.” Marine Geology 208:127–43.

Price, Richard, and Sally Price. 2021. Les Marrons en Guyane. Châteauneuf-le-Rouge: Vents d’ailleurs.

Prieur, Loïc. 2012. “L’accès au rivage.” Revue juridique de l’environnement spécial(5):93–103.

Rivet, Paul. 1913. “La protection des indiens au Brésil.” Journal de la société des américanistes 10(2):687–91.

Rivière, Peter. 1984. Individual and Society in Guiana. A Comparative Study of Amerindian Social Organization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Russell, Lynette. 2018. “Looking Out to Sea: Indigenous Mobility and Engagement in Australia’s Coastal Industries.” Pp. 165–84 in Indigenous Mobilities, Across and Beyond the Antipodes, edited by R. Standfield. Canberra: ANU Press.

Salazar, Gonzalo, and Paloma González. 2021. “New Mobility Paradigm and Indigenous Construction of Places: Physical and Symbolic Mobility of Aymara Groups in the Urbanization Process, Chile.” Sustainability 13(8):4382.

Sanchez, Jean-Lucien. 2014. “L’abolition de la relégation en Guyane française (1938-1953).” Criminocorpus. Revue d’Histoire de la justice, des crimes et des peines. http://journals.openedition.org/criminocorpus/2727

Sommer-Schaechtelé, Alexandre. 2023. “Perspectives de Guyane française : les peuples autochtones face à l’exploitation industrielle de la nature en Guyane française.” Les Cahiers du CIÉRA (22):121–26.

Santos, Fabio. 2020. “From French Guiana to Brazil: Entanglements, Migrations and Demarcations of the Kaliña.” Espace Populations Sociétés. Space Populations Societies (1-2).

Stock, Mathis. 2004. “L’habiter comme pratique des lieux géographiques.” Revue électronique des sciences humaines et sociales.

Stock, Mathis. 2006.“L’hypothèse de l’habiter Poly-Topique : Pratiquer Les Lieux Géographiques Dans Les Sociétés à Individus Mobiles.” https://www.espacestemps.net/articles/hypothese-habiter-polytopique/.

Toorman, Erik A., Edward Anthony, Pieter Augustinus, Antoine Gardel, Nicolas Gratiot, Oudho Homenauth, Nicolas Huybrechts, Jaak Monbaliu, Kene Moseley, and Sieuwnath Naipal. 2018. “Interaction of Mangroves, Coastal Hydrodynamics, and Morphodynamics Along the Coastal Fringes of the Guianas.” Pp. 429–73 in Threats to Mangrove Forests : Hazards, Vulnerability, and Management, Coastal Research Library, edited by C. Makowski and C. W. Finkl. Cham: Springer.

Trujano, Carlos Yescas Angeles. 2008. Indigenous Routes: A Framework for Understanding Indigenous Migration. Geneva: International Organization for Migration (IMO).

Uitermark, Cecilia. 2021. “Diasporic Indigeneity: Surinamese Indigenous Identities in the Netherlands.” The Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø.

Vidal, Lux Boelitz. 2023. Narrativas e Memória de Um Chefe Galibi Do Oiapoque- Récits et Mémoires d’un Chef Galibi de l’Oyapock. São Paulo: Iepé.

Vries, Ellen de. 2005. Suriname Na de Binnenlandse Oorlog. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers.

[1] This PhD research, conducted between 2019 and 2024, is called “Modes of dwelling, coastal dynamics and the production of cross-border coastal territory by the Kali’na of the lower Maroni River since 1950s”. This dissertation examined how territorial production emerges through the interplay between Kali’na dwelling practices and the socio-environmental dynamics of the Lower Maroni.

[2] In the broad sense, this term can refer to the descendants of any population brought into former European colonies. In French Guiana, it refers to people of mixed African and European descent born in the territory (Jolivet 1997), particularly those whose African ancestors were enslaved.

[3] In France, prefects are appointed by the central government to administer regions and departments, where they embody the authority of the executive and ensure the implementation of national policies at the local level.

[4] The ZDUC (Zone of Collective Use Rights) is a legal tool created by French law to align with the collective land tenure systems practiced by the Indigenous peoples of French Guiana, including the Kali’na. Under this framework, residents do not hold private land ownership; instead, they are granted usufruct rights over state-owned land, enabling them to pursue traditional subsistence activities such as hunting, fishing, and gathering, as well building their homes. In 1992, a ZDUC covering an area of 18,390 hectares was officially granted to the Kali’na of Awala-Yalimapo by a prefectural decree (Davy et al. 2014, 2016).

[5] See article 1 of French Constitution of 1958 : https://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/le-bloc-de-constitutionnalite/texte-integral-de-la-constitution-du-4-octobre-1958-en-vigueur

[6] Fundação Nacional dos Povos Indígenas.

[7] In 1975, Suriname became independent from the Netherlands, but the country went through political and economic crisis that led to a dictatorship and then a war. In Dutch literature and in the collective memory of Surinamese people, this conflict is known as “binnenland(se) oorlog”, referring to the “binnenland” (the interior of the country where most of the rebels and conflicts were located). Authors writing in English and French often refer to the armed conflict as a « civil war » which in Dutch is translated as « burgeroorlog » (Hoefte 2014). I use a direction translation of the Dutch terminology “binnenlandse oorlog” here.

[8] The Djuka people (or Ndyuka and also known as Aukan or Okanisi) are one of the six Maroon ethnic groups that are settled between Suriname and French Guiana. These Maroons groups are descendants of former enslaved African people who escaped from the plantations of Suriname during the 17th and 18th century. From late 18th century onwards, the Kali’na coexisted in the lower Maroni River region alongside the Maroons (Hurault 1961; Moomou 2011; Price and Price 2021).

Author :

Marquisar JEAN-JACQUES est géographe et chercheuse indépendante